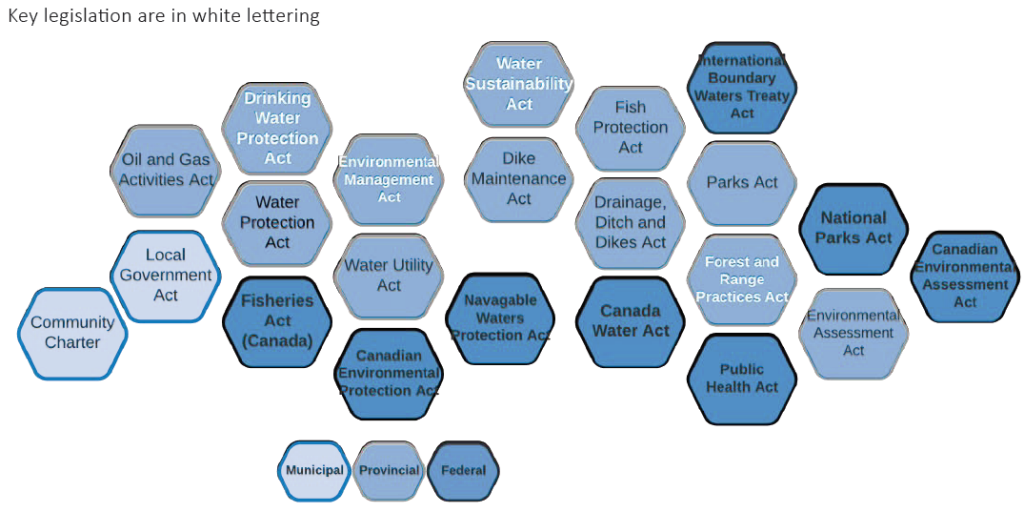

The governance of water use, protection, conservation, and sustainability in BC involves 22 pieces of legislation and various ministries and agencies at the federal, provincial, and local levels (see Figure 5).

See Chapter 2 of the Provincial Health Officer’s 2019 Clean, Safe, and Reliable Drinking Water report for more information on roles and responsibilities in drinking water protection in BC.

Figure 5: Legislation relevant to water in BC by level of government – 2021

Key legislation related to source water protection

Of the all the laws and regulations associated with drinking water protection, the Drinking Water Protection Act (DWPA), Water Sustainability Act (WSA), Forest Range and Practices Act (FRPA), and Environmental Management Act (EMA) have the most influence on source water protection.

Drinking Water Protection Act

The DWPA provides the legislative tools to respond to drinking water health hazards that can occur in watersheds and aquifers (it has the strongest powers to protect drinking water). All health authorities in B.C. employ Drinking Water Officers and Environmental Health Officers who provide education, advocacy, and enforcement of the DWPA. The health authorities work with B.C. ministries, local governments, water suppliers, and other stakeholders to improve source water protection and to reduce risk for residents and visitors.

Under section 29 of the DWPA, persons concerned about threats to drinking water can request that a DWO investigate the matter. Threats could include activities that are a contravention of the DWPA or activities that are determined to be a Drinking Water Health Hazard. Once a written request detailing the specific, factual reasons for investigation has been submitted, the DWO must review it and consider if an investigation is warranted. Under section 25 of the DWPA, a DWO may issue hazard abatement and prevention orders if they have reason to believe that a drinking water health hazard exists – meaning, any condition or thing related to drinking water that does or is likely to endanger public health, or prevent or hinder the prevention or suppression of disease.

Finally, Part 5 of the DWPA allows for the creation of a Drinking Water Protection Plan (DWPP). This is a last resort legislative source protection tool that may designate local authorities with powers to control activities in areas of concern. DWPPs have stringent requirements and are only be considered when all other options to address or prevent threats have been exhausted, including other plans or regulatory tools.

Water Sustainability Act

The WSA is the main law for managing the use and diversion of water. Under the WSA, water dedicated for agriculture can be protected in Agricultural Water Reserves, established as part of Water Sustainability Plans. The WSA also enables the establishment of water objectives for a watershed, stream, aquifer, or other specified area or environmental feature to sustain water quantity and quality for specific uses or to sustain aquatic ecosystems. There is also now a legal requirement under the WSA to set aside enough water for the health of riparian areas and the aquatic environment. Advancing Freshwater Protection summarizes how to use Water Sustainability Plans and other tools within the WSA to advance water sustainability.

Forest and Range Practices Act and Forest Planning and Practices Regulation

The FRPA is the most pertinent legislation impacting source protection on Crown lands. It outlines how all resource-based activities are to be conducted. The FRPA regulates the activities of forest companies and ranching operations on Crown land, including in Community Watersheds, through 12 regulations that detail government objectives to safeguard water and set practice requirements to protect water quality, riparian areas, and soils. Government objectives in Community Watersheds only apply after water treatment has occurred and to the extent that it does not unduly reduce the supply of timber or ranching area in B.C.’s forests.

Under the FRPA, requirements for the protection of drinking water vary by forest and range practice and by the type of licence. For example, forest licensees who must prepare a forest stewardship plan have different requirements than forest licensees who hold a woodlot licence. Some requirements may only apply to community watersheds[1] while others may apply generally to all watersheds. Each activity has rules contained in applicable regulation, including objectives and practice requirements for various values. The objectives define what government wants to achieve for the protection of specific values, and the practice requirements are rules that must be followed on the ground.

When they are working in a community watershed, a forest licensee must include results or strategies in their forest stewardship plan about how they will address government’s objective for community watersheds. The objective is stated in section 8.2 of the Forest Planning and Practices Regulation. Typically, forest licensees will commit to retaining a professional hydrologist to prepare an assessment about how the harvesting of cutblocks and the construction of roads will affect water.

The primary practice requirement for the protection of drinking water is contained in section 59 of the Forest Planning and Practices Regulation. This rule requires forest licensees to ensure that practices do not cause material(s) that are harmful to human health to be deposited in, or transported to, water that is diverted for human consumption by a licensed waterworks (e.g., petroleum products, fertilizers). Under subsection 60(1), forest licensees must also ensure their practices do not cause damage to a licensed waterworks. Both requirements apply to all ‘licensed waterworks’, whether or not they are located within or outside a community watershed. Also, section 84 requires that licensees must give at least 48 hours notice to a water supplier before building a road in a community watershed.

[1] These are watersheds where government has decided that special forest management is required in the watersheds to protect water used for drinking. The Okanagan has the highest number of community watersheds in BC.

Environmental Management Act

The EMA protects drinking water by regulating pollutants and industries that may contaminate water supplies. Under the Act, ENV works to prevent pollution and to promote and restore environmental quality, through the development of ambient water quality guidelines and water quality objectives and through the authorization to discharge waste subject to requirements to ensure the discharge adequately protects human health and the environment.

Legislative obstacles and how to overcome them

The myriad of regulations and agencies involved in water management creates obstacles to source water protection. Legislative obstacles and ideas on how to overcome them are presented in Table 19.

Table 19: Legislative obstacles and innovations to help overcome them

Obstacles

No clear hierarchy of authority or lead agency for source water protection on Crown lands; no inter-agency coordination in areas of jurisdictional overlap

Innovations

Identify a lead agency that is responsible for integration of water legislation and has authority over source water protection. Develop inter-agency coordination in areas of jurisdictional overlap.

Uncertainty around provincial direction

Request a progress report on source water protection from the Province.

No long-term (20-year) Response Plan on source water protection

Develop a clear actionable timeline and plan for source water protection with clear lines of responsibility and effective inter-agency collaboration.

No universal source protection metrics

Collate metrics and identify consistent indicators of safe drinking water that align with the multiple-barrier approach. Follow Quality Standards provided in Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality and the CCME standards.

Inconsistent funding for watershed planning and protection

Establish stable funding for watershed planning and protection. Consider user-pay.

Heavily entrenched groups and interagency groups have disbanded

Improve and maintain regular communications among all tenure holders and stakeholders, using shared risk and responsibility accounting.

Accountability, communication, and collaboration gaps among stakeholders

Improve and maintain regular communications among all stakeholders, using shared risk and responsibility accounting.

Vagueness of DWPA on time-delayed and cumulative contaminants

Further develop tools to assure that the WSA and DWPA align with Canadian Drinking Water Standards.

References: Okanagan Water Stewardship Council 2020; Brandes et. al. 2017; Auditor General for Local Government 2018.