This tool will to help you identify and value green infrastructure and natural assets in your community.

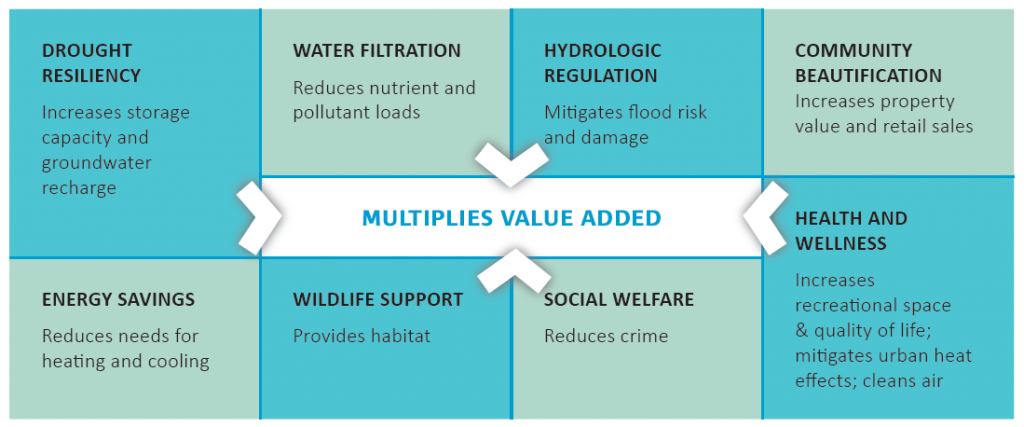

Source water protection is about protecting and restoring the forests, riparian areas, wetlands, waterways, floodplains, and soils that provide natural filtration and hydrologic regulation in watersheds (‘natural assets’). It is also about creating rain gardens, bioswales, green roofs, treatment ponds, and other enhanced and engineered ecological assets to manage stormwater in cities (‘green infrastructure’).[1] Green infrastructure and natural assets can also provide aesthetic, cultural, recreation, and tourism benefits and opportunities for harvesting of food and medicine (see Figure 4 to learn about more benefits).

Asset management processes have traditionally been applied only to engineered infrastructure. This tool provides information on how to map, inventory, valuate, and monitor the natural assets that provide ecological and hydrological functions and processes for managing water in your community. Significant strides have been made in natural asset valuation and management in B.C. and across Canada. Learning from other communities will contribute to your success. More information on valuation is provided in RESOURCES – Economic Benefits of Source Water Protection.

Figure 4: Benefits of green infrastructure and natural assets

How to use this tool

Including natural assets in asset management processes is not about treating engineered and natural assets in exactly the same way. An inventory of engineered assets may include different attributes than an inventory of natural assets; depreciation of natural assets and engineered assets will not be determined in the same way – and in some cases, natural assets can appreciate over time. The aim is to include information about natural assets in your overall asset management process so you can evaluate trade-offs between service, cost, and risk.

The Municipal Natural Assets Initiative (MNAI) offers a methodology to help local governments identify, value, and manage natural assets within traditional financial and asset management planning frameworks. As of 2021, 11 communities have piloted the MNAI approach, and some of their stories are included in the case studies at the end of this section. Other urban communities in B.C. have focused on green infrastructure planning – the City of Vancouver’s Rain City Strategy and Metro Vancouver’s Connecting the Dots: Regional Green Infrastructure Network Report are excellent examples.

Pro Tip: Prioritize the protection and restoration of riparian areas. They can serve multiple functions for drinking water protection, and the costs avoided from keeping them functional will save money in the long run. See RESOURCES – Economic Benefits of Source Water Protection for important information on how to do this.

If your community is evaluating natural assets or green infrastructure, or both, follow this general 5-step process.

Step 1: Develop a Policy and Set Goals

Develop an asset management policy, bylaw, or financial statement that includes green infrastructure and natural assets and define how they will help accomplish stormwater management or other source protection goals. See RESOURCES – Economic Benefits of Source Water Protection for ideas. Identify collaborative opportunities within your organization and within the broader watershed to maximize the benefit to other community services. Include internal and external subject matter experts and stakeholders with varying views on ecosystem services (including cultural services) from the beginning.

Step 2: Inventory and Map Green Infrastructure and Natural Assets and Identify Services

Create an inventory and map of green infrastructure and natural assets within your supply area – even where you don’t have jurisdiction such as upper watersheds. While it may not be feasible to map small-scale green infrastructure like rain barrels and cisterns, larger elements like trees, parks, and ponds should be included. Think about the services the green infrastructure and natural assets provide. Compile the information into an asset register like you would do for engineered assets. See this Primer for an example of an asset register.

Step 3: Determine Condition and Value

Identify the current and future risks to the green infrastructure and natural assets. Assess activities that have degraded, or will likely degrade, the function of ecological services provided by key assets (e.g., riparian area grazing, land development plans, wildfire, resource extraction, urban landscape lacking vegetation) and how they impact source protection goals. Determine the condition of your green infrastructure and natural assets by looking at existing studies (e.g., stormwater master plans, drainage studies, source water assessments) and by gathering existing monitoring data (e.g., flow monitoring, surface level monitoring, groundwater monitoring, data on soil types). Assign value to your natural assets (see RESOURCES – Economic Benefits of Source Water Protection for ecosystem valuation and techniques).

Step 4: Rank and Prioritize

Rank the natural assets based on identified risks and source protection goals. This will you help you determine which initiatives to prioritize. See this Primer for an example of an asset ranking.

Step 5: Look for Opportunities and Implement Actions

Step 5 involves three possible action paths:

- Identify and carry out the actions needed to improve the function of high-risk natural assets and green infrastructure;

- mitigate the future degradation of priority natural assets and green infrastructure;

- and increase the capacity of the natural assets and green infrastructure to meet source protection goals.

Potential actions could include the development of stringent bylaws, restoration of key habitats, acquisition of lands, incentive programs to encourage on-site water harvesting, and riparian fencing projects in upland watersheds and rural areas.

Watershed failures

Natural systems have ecological limits. When hydrology is altered through wildfire, loss of forest canopy, increase of impermeable surfaces, removal of wetlands, or loss of riparian vegetation, ecosystem services are diminished. The result is more intense floods, poor water quality—and communities ultimately pay.

For example, an improperly designed road and a storm resulted in a slope failure in the Belgo watershed that caused turbidity to soar at Black Mountain Irrigation District’s Mission Creek intake in May 2017.

[1] Definitions for ‘green infrastructure’ and ‘natural assets’ vary. In this toolkit, we define ‘green infrastructure’ as human-designed infrastructure (e.g., rain gardens, green roofs) that attempts to mimic nature and maintain connectivity with natural systems, and ‘natural assets’ as natural resources and ecosystems (e.g., riparian areas, forests) that yield benefits to people.

Case Studies

Comox Lake Initiative Strengthens Role of Nature in Protecting Drinking Water

READ ARTICLE: Comox Lake Initiative Strengthens Role of Nature in Protecting Drinking Water In 2019, several Comox Valley communities and the K’òmoks First Nation launched a multi-year initiative with the Municipal…

k’əmcnitkw (Alongside the Water) Floodplain Re-engagement Project

Located on Penticton Indian Band Reserve # 1 bordering sn’pink’tn (Penticton), BC, this innovative, multi-year, multi-partner project is well on-track in its efforts to restore the biodiverse mosaic of shallow…

City of Kelowna Roadside Bioretention

The City of Kelowna is looking at new ways to use green infrastructure to manage water on roadways. Rather than typical curb-and-gutter systems used along most Kelowna roadways now, the…

The Town of Gibsons’ Experience in Financial Planning and Reporting

The Town of Gibsons was North America’s first community to experiment with strategies to integrate natural assets into asset management and financial planning. They started in 2009 by valuing the…

More on Municipal Natural Asset Management

Click here to read other case studies related to municipal natural asset management.

Measuring the Value of Natural Assets in Saskatoon

READ ARTICLE: Measuring the Value of Natural Assets in Saskatoon The City of Saskatoon completed a pilot project to assign measurable value of the ecosystem services provided by its natural assets….

Links

Integrating Natural Assets into Asset Management published by Asset Management B.C. in 2019. https://www.assetmanagementbc.ca/wp-content/uploads/Integrating-Natural-Assets-into-Asset-Management.pdf

The Partnership for Water Sustainability in B.C., 2019. Primer on the Ecological Accounting Process (EAP): A Methodology for Valuing the “Water Balance Services” Provided by Nature. https://waterbucket.ca/gi/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/07/Primer-on-Ecological-Accounting-Process_Jan-2019.pdf

Natural Asset Primer published by the Municipal Natural Asset Initiative in 2018. https://mnai.ca/media/2018/01/FCMPrimer_Jan1_2018.pdf

Constructed Wetlands for Stormwater Management: An Okanagan Guidebook prepared for the OBWB by Associated Environmental in 2018. https://www.obwb.ca/newsite/wp-content/uploads/2018_constructed_wetlands_guidebook.pdf

What are Municipal Natural Assets: Defining and Scoping Municipal Natural Assets (2019). https://mnai.ca/media/2019/07/SP_MNAI_Report-1-_June2019-2.pdf

The Trust for Public Land and American Water Works Association Source protection handbook. Using Land conservation to protect drinking water supplies https://www.tpl.org/sites/default/files/cloud.tpl.org/pubs/water_source_protect_hbook.pdf

Putting a Value on Ecological Services https://waterbucket.ca/gi/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/07/Primer-on-Ecological-Accounting-Process_Jan-2019.pdf

Asset Management for Sustainable Service Delivery – A B.C. Framework 2019 https://www.assetmanagementbc.ca/wp-content/uploads/Asset-Management-for-Sustainable-Service-Delivery-A-BC-Framework-.pdf

Parrott, L. and Kyle, C, 2014. The Value of Natural Capital in the Okanagan. http://complexity-ok.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2014/10/The-value-of-natural-capital-in-the-Okanagan.pdf